By Robert J. Barro

The best source of a worst-case scenario for the ongoing coronavirus pandemic likely comes from the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1920. Our research[1] found from data on 48 countries that the flu death rate averaged 2.1 percent, corresponding to 40 million worldwide deaths. When applied to current population, this death rate implies a staggering 150 million deaths worldwide.

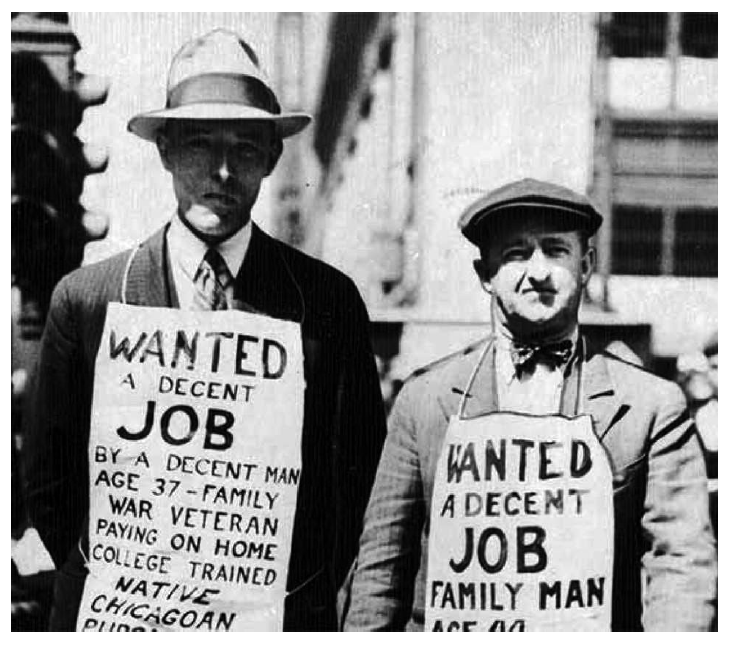

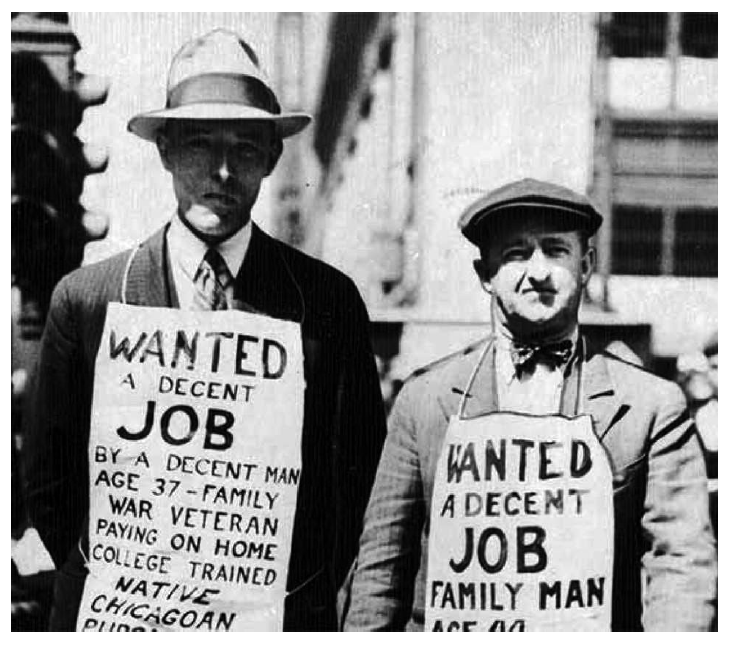

The 1918-1920 pandemic was associated with recessions in many countries. The average size of the contraction in GDP was about six percent, lasting around two years; that is, the lost output was about 12 percent of a year’s GDP. To put this outcome in a broader context, my research on rare macroeconomic disasters showed that the three worst global macroeconomic crises were WWII, the Great Depression of the early 1930s, and WWI. (The U.S. was an outlier in having grown rapidly during WWII.) The Great Influenza may have been the next worst global adverse event going back to 1870. Around 12 or so countries out of 42 with data were estimated to have suffered declines in real per capita GDP by 10% or more with troughs in 1919-21.

Currently, the main policy being followed in most countries to counter the coronavirus pandemic is to curb economic activity as a way to reduce interactions and contagion. This policy amounts to a decision to reduce world GDP in the short run by roughly 20 percent at an annual rate. A decline in GDP by 20 percent, if it lasts for a full year or more, would constitute a rare macroeconomic disaster, worse than that associated with the Great Influenza. However, the reasonable hope in the current environment is that the sharp cut in the flow of output will last for only a few months, after which the virus will be contained. That is, the objective is for a sharp, V-shaped recovery. For example, if the cut in GDP lasts for only six months, then the lost output would be only 10% of a full year’s GDP.

What are reasonable monetary and fiscal responses to the fall in GDP? Since society, represented by its political leaders, has determined that the cost of reduced GDP is worth bearing as a way to combat the pandemic, it would be inconsistent to follow the usual stimulus policies that work by raising aggregate demand and, thereby, increasing real GDP. For example, if aggressive monetary policy—cutting short-term nominal interest rates and raising central bank purchases of assets—succeeds in raising GDP, we would not regard that as success in the current unusual environment. If we did not want GDP to fall by 20 percent, we could have achieved that goal in the first place by lessening the constraints on economic activity.

The same argument applies to a general fiscal expansion; for example, the U.S. policy of having the federal government give most adults a check for $1200. To the extent that this kind of policy succeeds in raising aggregate demand and, thereby, GDP, we have the same situation as with aggressive monetary policy. That is, we would not value the offsetting rise in GDP. In fact, the aggressive fiscal and monetary policies that have recently been implemented in the United States are likely to be highly inflationary. Thus, we may finally move away from the remarkably successful low and stable inflation that has been in place in most countries since the late 1980s.

More reasonable are targeted policy responses aimed partly at individuals and partly at businesses. One dimension of this policy is strengthening the existing social-safety net. In this context, it makes sense to increase accessibility and benefit levels for programs like unemployment insurance, food stamps, and Medicaid (which finances medical expenses for poor persons). These program expansions, some of which are in the recent U.S. package, are much more targeted to the needy than is the passing out of $1200 checks to everyone.

It also makes sense that the recent U.S. package includes policies aimed at limiting the permanent disappearance of businesses and maintaining links between firms and their workers. Much of this response applies to particularly distressed sectors, such as airlines and other travel-related companies. It is also crucial for central banks, including the U.S. Federal Reserve, to avoid major disruptions of financial markets. These actions are already being pursued vigorously, and they provide confidence that the financial disruptions during the Great Recession of 2008-2009 will not be repeated.

I do not find that the Great Influenza Pandemic caused permanent structural changes in the macroeconomy or in government policies, although the later Great Depression and World War II did have these kinds of effects. I think that the ongoing coronavirus crisis will be similar to the Great Influenza and will have no great impact on the structures of economies. Yet, there will be some permanent changes. For example, countries such as the United States will be less willing to rely on foreign suppliers for goods and services regarded as crucial during a crisis. Part of this change will involve further movement away from China as a source of many products. And some industries, such as airlines, will likely change permanently, notably in terms of maintaining a greater degree of social distancing among passengers. The practice of shaking hands will likely also become a thing of the past.

Robert Joseph Barro

Robert Joseph Barro is an American macroeconomist and the Paul M. Warburg Professor of Economics at Harvard University. Barro is considered one of the founders of new classical macroeconomics, along with two Nobel laureates Robert Lucas, Jr. and Thomas J. Sargent.

The Chinese version of this article is published in PKU Financial Review

【1】Robert J. Barro, José F. Ursúa, and Joanna Weng, “The Coronavirus and the Great Influenza Pandemic: Lessons from the ‘Spanish Flu’ for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity,” National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 26866, March 2020.