By Andrew Sheng / Xiao Geng

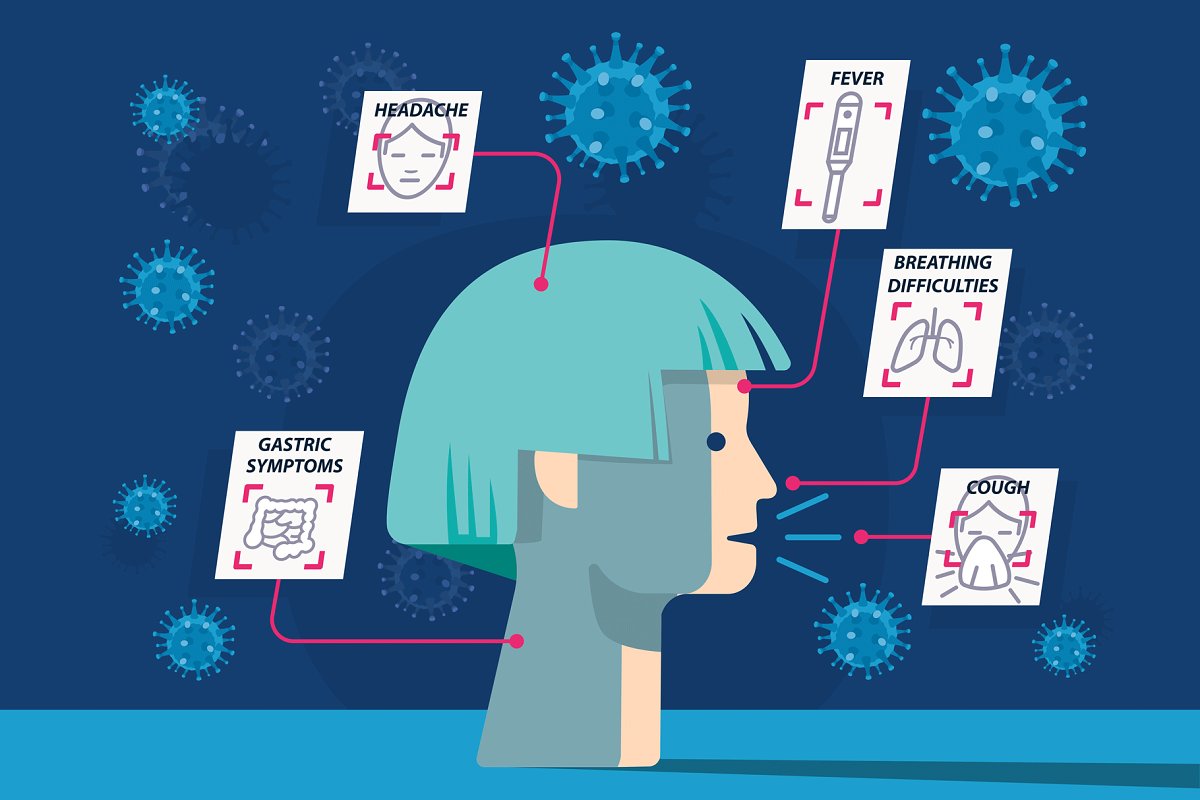

Sheltered by umbrellas, well-prepared protesters, in clear labor divisions, are dismantling metal barriers from the roadside in Causeway Bay, one of Hong Kong's business districts, on Sunday. [Photo/China Daily]

Hong Kong has long been a beacon of inspiration for other Asian cities. Highly competitive and connected, it has served as a bridge between the East and the West, earning it the moniker "Asia's world city". But this position is now under threat-and it is Hong Kong's own fault.

For several months, Hong Kong has been seized by protests that began against a bill to amend the extradition law. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region's government has dropped the bill but the protests have continued.

HK at risk due to its own insecurities

Hong Kong's advantages are now at risk, largely due to its own insecurities. As several commentators have pointed out, the Chinese mainland's remarkable economic growth and development has eroded Hong Kong's status as a leading center for finance, logistics and trade. In 1997, when Hong Kong was reunited with the motherland, the city handled half of the mainland's foreign trade, and its GDP amounted to nearly one-fifth of the mainland. It far outperformed Shanghai-the mainland's most prosperous city-in terms of GDP, per capita income and shipping volume.

Today, Hong Kong accounts for just one-eighth of China's trade. In terms of GDP, it now lags behind not only Shanghai but also Beijing and Shenzhen. In terms of shipping volume, even a much smaller mainland city such as Ningbo outperforms Hong Kong.

Even more frustrating for Hong Kong residents, however, is the rising inequality in the SAR-a trend that has been exacerbated by the world's highest property prices. But it is local politics, not the central government, that has hampered the provision of more affordable public housing and impeded action to improve skills and employment opportunities.

When it comes to Hong Kong's economic and financial position, the central government's initiatives should help. In particular, the Greater Bay Area urban cluster, covering nine cities around the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, plus Hong Kong and Macao, holds great potential. Yet some in Hong Kong are resisting such integration, arguing that it will further erode their political autonomy, economic strength and local identity.

The question is why Hong Kong's (largely local) grievances have spurred such large-scale demonstrations.

Polarized social media facilitate mass action

The answer may lie partly in the internet-or, more precisely, in the digital echo chambers being created by social media. Hardly limited to Hong Kong, the phenomenon was a driving force behind the global wave of demonstrations in 2009-12: the Green Movement in Iran, the "Arab Spring" in the Middle East, Occupy Wall Street in the United States, and the anti-austerity protests in Portugal, Spain and Greece.

In his book Networks of Outrage and Hope: Social Movements in the Internet Age, social theorist Manuel Castells argues that such "multifaceted rebellions" were driven not so much by poverty, economics, or lack of democracy as by "the humiliation provoked by the cynicism and arrogance of those in power".

But it was only through networking that such emotions were translated into mass action. Those who felt humiliated by the powerful "ignored political parties, distrusted the media, did not recognize any leadership, and rejected all formal organization". Instead, they sought to exercise "counter power" by "constructing themselves… through a process of autonomous communication, free from the control of those holding institutional power".

Fear transformed into outrage

Social-media platforms facilitated this process. But in bringing together those with similar perspectives on local issues, they cut them off from opposing views. This fueled polarization, causing fear to be transformed into outrage, and in some cases, "outrage into hope for a better humanity".

Such horizontally networked, emotion-driven movements often give way to violence, as Hong Kong is now learning. Recently, protesters stormed and vandalized the Legislative Council building and, later, the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government in the Hong Kong SAR.

Such activities, together with the spread of demonstrations into local districts, leave police stretched to their limits. This puts the protesters themselves in danger: days ago, dozens of masked men armed with batons attacked people returning from a demonstration at a metro station. Forty-five people were hospitalized-one critically.

In this highly charged and deeply polarized atmosphere, preserving Hong Kong's position as a stable and reliable bridge between the mainland and the rest of the world will not be easy. But it is in everyone's interest. The first step will be to conduct a serious discussion on the "one country, two systems" framework, especially on how to balance the autonomy promised by "two systems" with the sovereignty guaranteed by "one country".

In this process, Hong Kong people must make a vital calculation. As the most international part of China, Hong Kong has a major role to play in shaping China's ongoing global integration and encouraging openness. If it abdicates this role, the central government will forge ahead anyway, only that Hong Kong will be left behind.

Xiao Geng, president of the Hong Kong Institution for International Finance, is a professor and director of the Research Institute of Maritime Silk Road at Peking University HSBC Business School.

Andrew Sheng is a distinguished fellow of the Asia Global Institute at the University of Hong Kong and a member of the UNEP Advisory Council on Sustainable Finance.

Project Syndicate