In recent years, the robotics industry has achieved rapid development driven by both technology and demand. The prospect of the market demand for elderly care robots brought about by the increasing demand of aging population is considered to be one of the hot topics in the future. However, existing researches point out that the unemployment caused by industrial robots has the characteristics of "the poor get poorer", namely, people with lower education levels may become the "losers" in the wave of artificial intelligence.

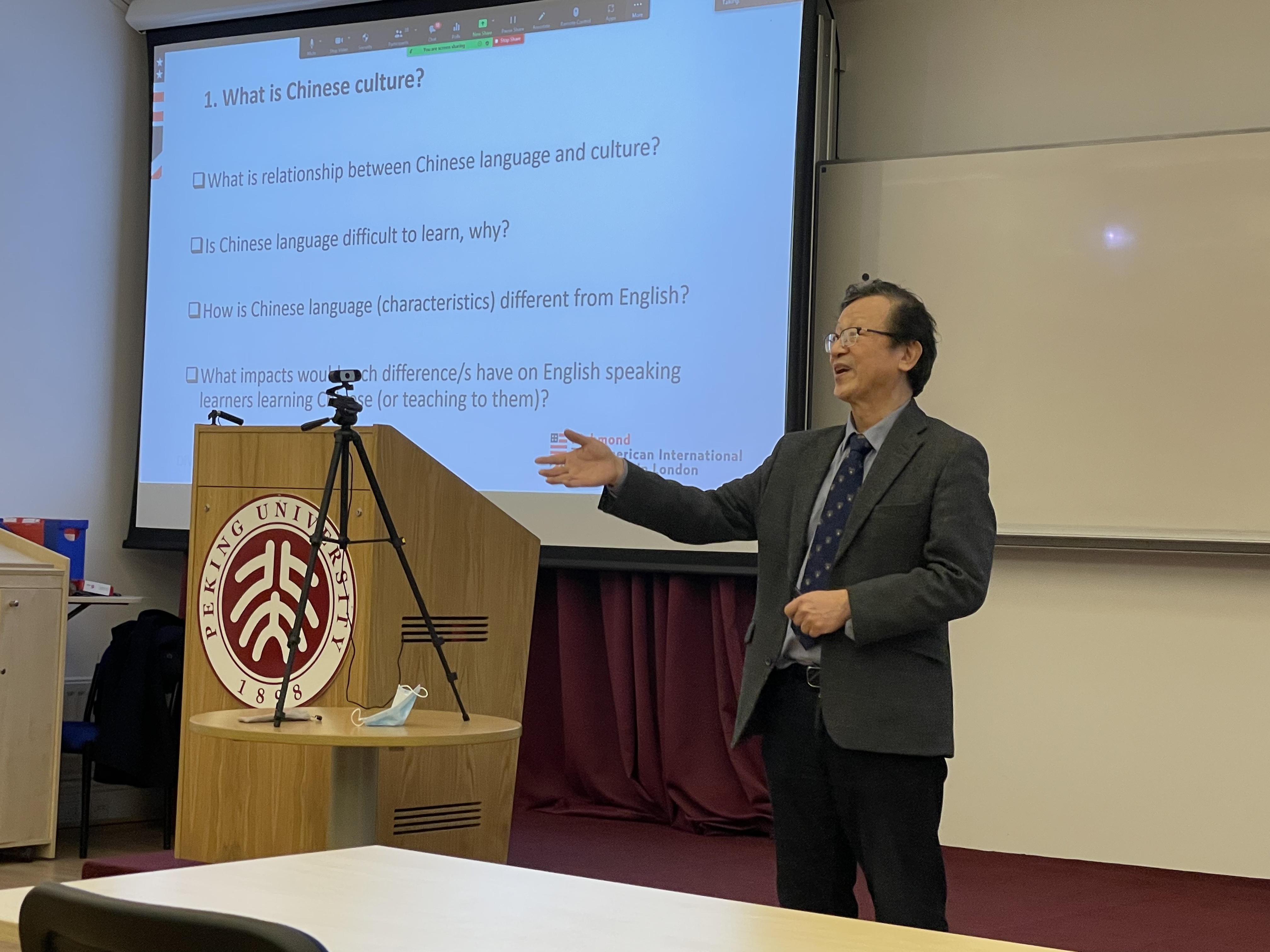

In the interview with PKU Financial Review, Richard B. Freeman, an American economist, the Herbert Ascherman Professor of Economics at Harvard University, Co-Director of the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities, and Co-Director of the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School, states that Whether the gains in productivity and output from blue collar and service sector worker automation and from white collar worker automation balance out losses in jobs to the machines and improve worker and pensioner incomes depends in part on who owns the robots or the income flowing from them and rates of taxation on capital income and labor income. If a small number of wealthy persons own the robots and pay modest capital gains taxes on their increased wealth, they will be the primary beneficiary, and the rest of society will gain little. The wider the spread of ownership, the more likely will automation benefit all.

PKU Financial Review: China is one of the fastest aging countries in the world. What do you think of the impact of China's aging on economic growth? What measures can be taken to reduce the negative effect of aging?

Richard B. Freeman: China's aging will reduce its growth rate into the foreseeable future and probably reduce the rate of innovation as well, given the importance of young scientists, engineers, inventors, and entrepreneurs to innovation. There are three potential ways to offset the adverse growth effect of an aging population: 1) the development of robots and other machines, including AI software, to substitute for human labor; 2) increased education of younger workers, so that they substitute greater labor quality for the reduction in relative numbers; and 3) opening routes to immigration to add many young immigrants to the work force.

Japan has been in the forefront of developing machine substitutes for humans to deal with its aging problem. South Korea has pushed higher education. The US has historically relied on immigrants, attracting many educated persons first as international students and then as immigrant workers, and gaining many immigrants from Mexico and Latin America. With the growth of robots and investment in AI, the huge increase in higher education, and both an increased number of international students and a large rural population that can migrate to jobs around the country, I would expect China to use policies in each of the areas to compensate for the aging population.

PKU Financial Review: In your paper "From Immigrants to Robots: The Changing Locus of Substitutes for Workers", you pointed out that unemployment caused by industrial robots has a trend of making the poor poorer. But robot automation may help the aging service industry to solve the problem of service labor shortages. Does this improve human welfare from another perspective? Overall speaking, what do you think of the overall welfare of robots to humans?

Richard B. Freeman: Many countries with aging populations face a declining ratio of the number of workers, whose taxes fund pay-as-you-go state pension funds, to the number of retirees whose living standards depend on state pension income. A falling ratio of workers to pensioners as the population ages poses grave problems to the financial viability and generosity of a pension system. But the ratio of capital in the form of robots and software to pensioners is increasing, potentially increasing GDP and taxes to sustain pension finance. The increase in robots is particularly large in China and the push for investments in AI should lead to better software that can increase national output and thus offers a way to improve the well-being of all citizens.

Whether the gains in productivity and output from blue collar and service sector worker automation and from white collar worker automation balance out losses in jobs to the machines and improve worker and pensioner incomes depends in part on who owns the robots or the income flowing from them and rates of taxation on capital income and labor income. If a small number of wealthy persons own the robots and pay modest capital gains taxes on their increased wealth, they will be the primary beneficiary, and the rest of society will gain little. The wider the spread of ownership, the more likely will automation benefit all. The higher the taxes on wealth and income, the greater will governments have sufficient funds to boost pensions even as job losses to machines reduce the flow of income into pension plans.

There are, of course, alternative ways to maintain the viability of a pay-as-you-go pension system as the population ages and the number of pensioners increases, --most importantly through work longer/retire later policies.

PKU Financial Review: Industrial robots exert great impact on labor market. What do you think of the impact of medical robots on the wages of medical staff? And the impact of educational robots (educational interaction and educational evaluation) on education market?

Richard B. Freeman: On medical and educational robots, there has been an increase in the use of technology – software and AI embodied in machines like robots and in other ways, such as on-line education – in most societies. Telemedicine expanded during the pandemic and in education with teaching, seminars and conferences replacing face-to-face medical and educational activities. I expect this to continue post the pandemic with some mixture of on-line and off-line medical and education services. AI should greatly improve the ability of our health and educational organizations to provide services to citizens.

PKU Financial Review: How do you think companies and organizations will respond to the change in an aging country? Will it increase investment in automation technology while reducing welfare policies (retirement extensions, pension policies, etc.)?

Richard B. Freeman: I expect firms to increase automation in an aging country, but do not see them reducing welfare policies that appeal to workers. They will be competing in the job market for human talent and it makes little sense to compete with reduced welfare policies. The policies I expect to expand are the “working longer/retiring later policies” in which firms will seek to attract young employees with good benefits, including pension plans, but that give incentives for the worker to stay longer at the job and retire later.

In China, where coming retirees have longer expected life spans than older generations of retirees, I would expect the government to do what many other governments have done and use tax incentives to encourage retirement extensions and to incentivize people to work up to a point after retirement. The experience of such policies in US and many other countries suggest that they indeed work.

In the US the federal government legislated in 1983 gradual increases in the full retirement age for persons born in and after 1960 from age 65 to 67 and smaller increases for persons born earlier. Incentivized to work two or so extra years, Americans aged 55 and older increased their labor participation by about 10 percentage points from 1989 to 2018. The average age of retirement increased from 64.2 to 67.9 years for men and from 63.4 to 66.5 years for women between 2003 and 2018.

Such policies work, however, only in so far as workers are healthy and able to work and firms have jobs for them. When lifespan differs greatly between blue collar and service workers and management and professional workers, there is an intrinsic unfairness to raising retirement ages uniformly: the loss of one year of retirement harms the well-being of persons with a shorter life span than those with a longer life span. Thus, working longer/retirement policies have to be carefully constructed for different groups to make them fair to all.

Richard B. Freeman

Co-Director of the Harvard Center for Green Buildings and Cities,

Co-Director of the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School

* This article has been translated and published in PKU Financial Review.