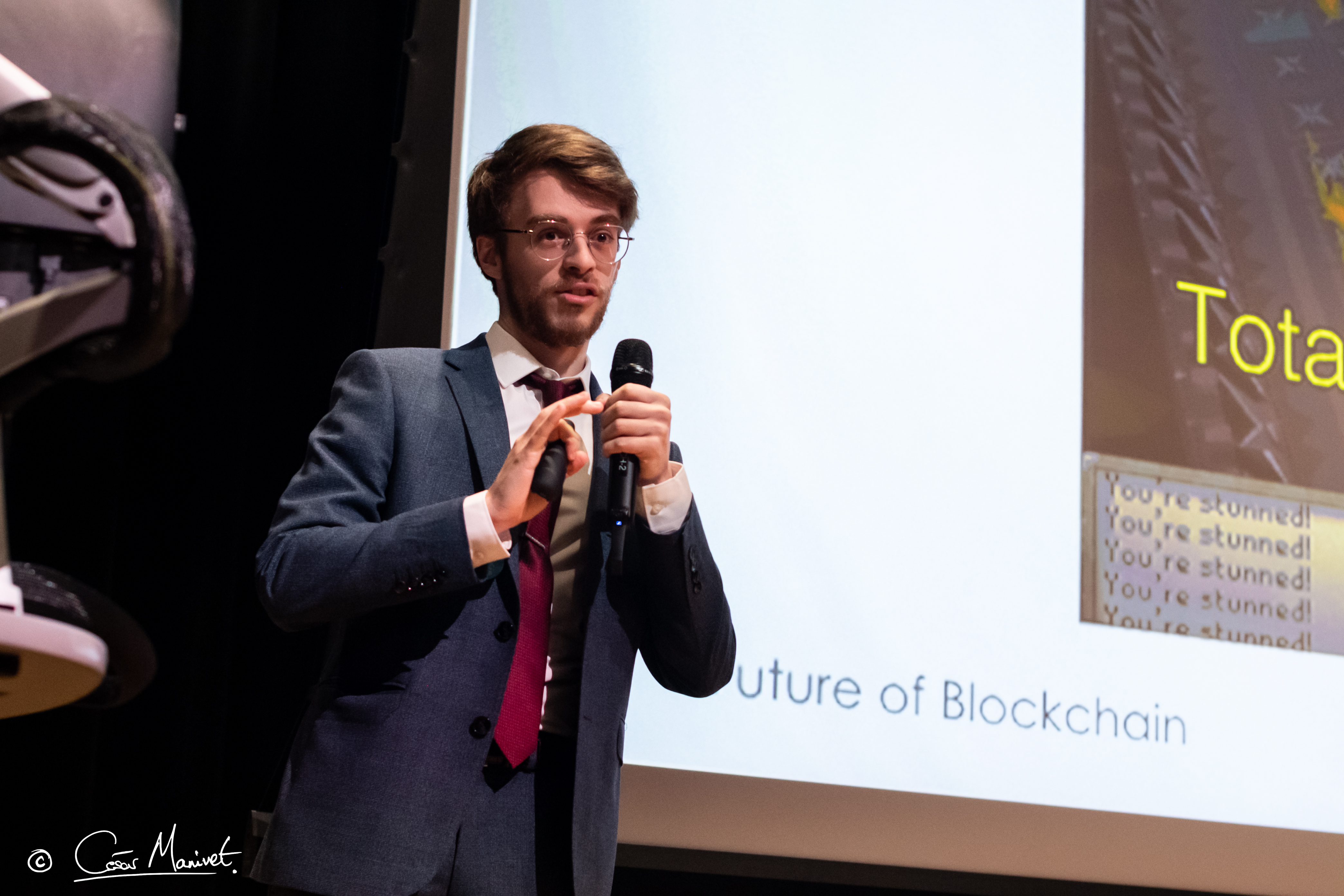

Regarding population aging, PKU Financial Review interviewed Charles Goodhart, the developer of "Goodhart’s law", Fellowship of the British Academy, & professor at the London School of Economics, and Manoj Pradhan, Funder of Talking Heads Macro & former Managing Director of Morgan Stanley. This article is their thinking and reply on a series of issues. They point out that in the future, global overall economic growth may decline significantly, but per capita GDP will outperform the overall GDP growth. They argue that there are at least two sources of capital flows that could make China's pension system larger: one is to "redistribute" the massive savings of state-owned enterprises, and the other is to allow more young labour force to be employed in formal sectors, in order to create a more regulated pension system.

PKU Financial Review: In your book The Great Demographic Reversal, you pointed out that in the long run, demographic changes will have a significant impact on global inflation. But we know that there are many factors that affect inflation. Then, how to study the impact of demographic factors on global inflation on the basis of controlling other variables? What effective measures are there to reduce its influence or slow down this trend?

Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan: In the last few decades there have been some remarkable demographic developments, especially in China. A baby boom (1945-65) was followed by a collapse in fertility with women shifting from housework to employment. Rising living standards and improved medicine has led increasingly to longer expectations of life, not matched by higher retirement ages.

These trends have been so strong that they have been swamping other influences on inflation, such as technological innovation and macro-economic policies.The effect of demography on inflation is hard to isolate, but any ‘true’ model will need to be global, and will need to include (i) the decline of labour unions and the bargaining power of labour, (ii) a multi-decade disinflation that led to falling inflation expectations, and (iii) the massive relocation of production to China. The traditional way of capturing the ‘China effect’ is to look at the share of China in a country’s imports, and to look at import prices. This creates a serious understatement of the effect of global demographic forces on domestic inflation.

What can be done to reduce the influence of ageing? The ‘silver bullet’ would be a cure for neuro-degenerative diseases, but that is more hope than reality. Perhaps the developing shortages of labour in China/Europe/North America can be allayed by switching production to regions with much faster growing working populations, such as Africa, but there are many (political) obstacles to this. This implicitly implies another era of globalization, which seems to be quite distant under current domestic political conditions in the advanced economies.

PKU Financial Review: China's demographic dividend is disappearing, which will not only affect China's future economy, but will also have a negative impact on the global economy. Regarding the effect of emerging technologies on economic growth, your attitude is not very optimistic. So, at a time when population aging has become an overall trend, how do you see the future global economic growth? Do you hold a pessimistic view?

Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan: Aggregate economic growth will decline, perhaps strongly. But productivity output per worker hour, will rise faster than before. As a result, per capita GDP will perform better than overall GDP growth.

The increased power of labour and the rise in interest rates will together help to lower inequality within countries. That’s a silver lining, but it will happen against a backdrop of weak growth.The main problem will be the rise in the ratio of retired old to workers. The workers will have to save, or be taxed, much more to release resources for looking after the elderly. That will be difficult.

PKU Financial Review: You pointed out that in the process of population aging, inequality will be magnified. In China, there is a huge gap between the pensions of urban and rural populations, and superior pension services can only be enjoyed by the wealthy. It is also the same in some developed countries. However, the tax system in developed countries is relatively complete. Does this mean that taxation will play a very limited role in reducing future inequality? In your opinion, what should the government and society do to promote "equity in the elderly"? How do you judge China's current "common prosperity" policy?

Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan: The fall in the birth rate has been so large that care of the elderly can no longer be done within the family group. Also the needs of the aged vary greatly and randomly. Those with the neuro-degenerative diseases of the old, and who live longer, will have needs that go beyond all reasonable personal savings. Whereas those who die suddenly at an earlier date can quite easily survive on sensible personal savings, an ageing society needs a form of age/sickness insurance system.

“Common prosperity” is a goal consistent with the social contract between the administration and the country’s residents. Having seen the struggles within the advanced economies because of inequality, it is natural that the administration should try and avoid that negative spillover from embracing market-based incentives for corporate China. However, to the outside world, the message surrounding “common prosperity” is muddled because it comes at the same time as China’s campaign against property speculation and the socially disruptive parts of the technology sector. Even though the common prosperity drive is sure to encourage philanthropy and greater social responsibility, it is unclear to outsiders whether this will happen at the expense of entrepreneurial incentives that the market system is designed to create, and whether limiting speculation and excesses in the property sector will also damage an important driver of China’s growth.

PKU Financial Review: As of the end of 2018, China's corporate contributions and private pensions were equivalent to 7.3% of its GDP, compared with 136% in the United States. Moreover, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences' earlier estimate in 2019 predicted that, China's national pension fund will be used up by 2035. With the rapid increase of China's aging population, how should China's pension model develop in the future? Where does the money come from?

Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan: Your retirement age is too low. You need to relate the retirement age to the expectation of life. You also need an insurance scheme, to which all must contribute, to pay out for those needing more care and living longer. Care homes need to be widely developed.

One question also often asked is whether it would be possible, or desirable, to raise the present low birth rate by policy measures. So far, attempts to do so in various European countries have been largely unsuccessful, and the more efficacious have involved financial subsidies for having more children, and are hence fiscally expensive.

There are at least two sources of financial flows that will allow China’s pension system to become bigger. First, the substantial savings that reside in China’s State Owned Enterprises could be ‘reassigned’ to help add to the pension pool, perhaps by financing debt obligations issued by the administration and used for elderly care. Second, China’s population pyramid has become a ‘barrel’-shaped structure, but the smaller number of young workers have substantially higher levels of human capital than the larger number of older workers who are retiring. As such, that should mean their employment is far more likely to be in the formal sector. Formal sector employment has a much greater ability to adopt and sustain pension systems. Effectively, the younger worker would end up creating a pension system for their own futures, while SOE savings could help finance at least part of the required increase in the pension pool for the elderly.

PKU Financial Review: You have pointed out that political conflicts are likely to occur between the main working-age population and the elderly: the key point of the future ageing struggle may be that the elderly defend their social welfare while the young defend their after-tax income. To a certain extent, the improvement of pension benefits means more "exploitation" of young people. In your opinion, will this further reduce the fertility rate, thus forming a vicious circle in the society?

Charles Goodhart & Manoj Pradhan: Demographers have not historically been successful in predicting future birth rates. But there are no signs yet of any recovery, rather the reverse, with rates falling further in the Covid pandemic. Anyhow, it would take 20 years for any up-tick in birth rates to affect the working age population. So hoping to raise the fertility rate is not going to address our current problems.

Instead we need a full discussion of how long retirement should last, and an insurance scheme for those most in need of care.As mentioned in previous comments, labour is likely to gain far more power, and China’s labour force in particular is likely to have a stronger bargaining position because of its higher stock of human capital per capita. The ability of workers to protect their own interests (i.e., demand higher after-tax wages) is one of the reasons that we expect inflation. On its part, the government cannot rely on (income) tax revenues to finance elderly care. That’s why so many ageing economies are projecting a huge increase in government debt. In order to avoid the same outcome, China’s administration has to bring its considerable abilities to focus on creating facilities and networks that will take care of the elderly. And it is has to start doing so today, not a decade from now.

Charles Goodhart (left) , the developer of "Goodhart’s law", Fellowship of the British Academy, & professor at the London School of Economics, and Manoj Pradhan, Funder of Talking Heads Macro & former Managing Director of Morgan Stanley.

* This article has been translated and published in PKU Financial Review.